“I’m very famous and pretty poor,” this ironic self-description is an effective summation of the rise and fall of Glauber Rocha. He was the most vocal and flamboyant exponent of Brazil’s Cinema Novo movement, which registered a powerful impact on 60's cinema. It's influence extended from Werner Herzog to Martin Scorsese, Jonathan Demme, Bernardo Bertolucci, Amos Gitai and Jean-Luc Godard (who would cast Rocha as an actor in his Le Vent d’est). Rocha’s films would become rare objects when the zeitgeist of the mid-60s receded and his career would struggle after his self-exile from Brazil following its decline into dictatorship. His early death at the age of 42 left behind a body of work that ranks among the most adventurous in film history.

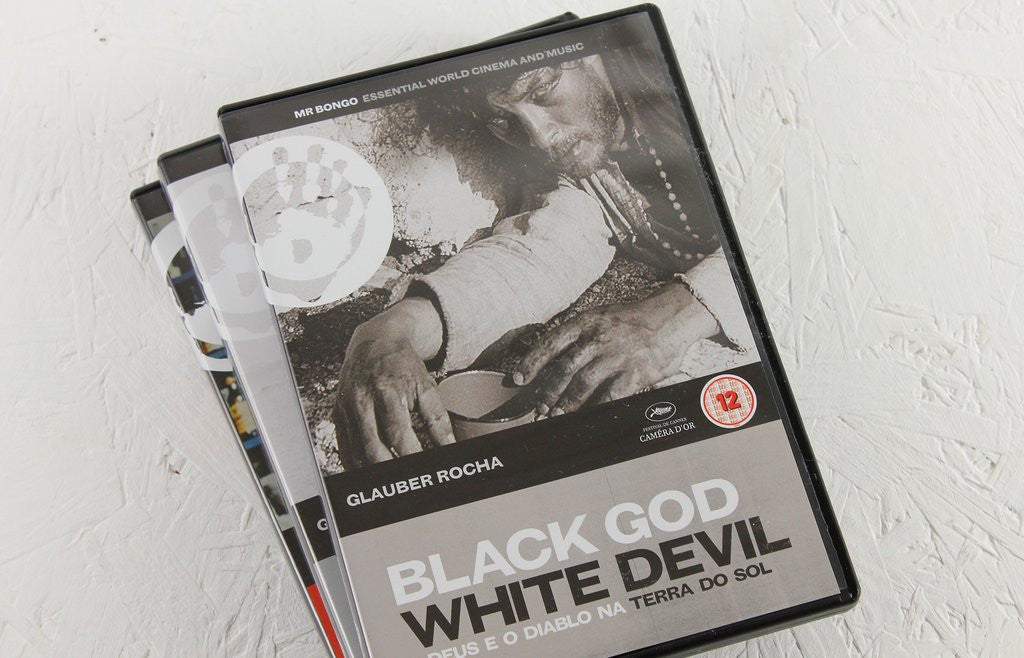

'Deus e o Diabo na Terra do Sol' (Black God, White Devil) was the first of Rocha’s “Westerns”. Set against the backdrop of Brazil’s sertão, it depicted the plight of Brazil’s poor classes by means of a bombastic style that pitched larger-than-life characters against each other in an allegorical discourse on good and evil. The film’s powerful images were matched by an equally stirring soundtrack that mixed music by J. S. Bach with songs by Heitor Villa-Lobos. Rocha’s Entranced Earth departed in genre from its predecessor, political thriller instead of allegorical western, but Rocha’s epic sensibility prevailed in his critique of the failure of intellectuals to mount a positive resistance against the widespread political corruption that enveloped the fictional “Eldorado”.

His bold post-colonial vision achieved greater clarity with his first colour film, 'Antonio das Mortes'. The title character served as an antagonist in 'Black God, White Devil'. However he immediately proved popular owing to his conflicted impulses as well as actor Mauricio do Valle’s performance. As such Rocha provided him with his own film, where the conflicted hitman would finally side with those he hunted and strike back at his former masters. The film’s visual beauty and the intensity with which Rocha tapped into the revolutionary fervor of the time made it his most famous film and most successful. It would receive an award for Best Director at the Cannes Film Festival, by a jury led by Luchino Visconti and would later be cited as a major influence by Martin Scorsese and Jonathan Demme.

The rise of military dictatorship in Brazil led Rocha to a period of self-exile. This period includes collaborations with French New Wave stars Jean-Pierre Léaud (Der Leone Have Sept Cabecas) and Pierre Clementi (Cabezas Cortadas) as well as a series of shorts, of which Di Cavalcanti is regarded among his best works. He would return to Brazil during President Ernesto Geisel’s tenure in the mid-70s. During this period Brazil’s military government made reforms that pushed towards gradual democratization. Rocha would briefly engage in direct political engagement before dedicating himself to the production of what would become his final film: The Age of the Earth. The film’s total break from any cinematic convention would make his 60s work seem accessible by comparison. Serge Daney, editor of Cahiers du Cinémamagazine, memorably described it as a “filmic flying saucer, no more, no less” while Michelangelo Antonioniwould state that “each scene [of the film] was a lesson in how modern cinema should be made”.

For Rocha, who hoped to recover Brazilian culture for its blighted people and who hoped to create a truly cinematic language separate from film and theatre, it proved to be the culmination of his life’s work and a fitting testament to a career free of compromise.