Federico Fellini was born in 1920 to a provincial middle-class family in Rimini, a small town on the coast of the Adriatic Sea. The lack of available options to young men in provincial towns is an important theme in some of his films, most notably I Vitelloni and Amarcord. In fact, Orson Welles once described Fellini as “a small-town boy who’s never really come to Rome. He’s still dreaming about it. And we should all be grateful for those dreams.” He initially arrived in Rome as a law student but his career as a satirical cartoonist and gag writer was already well established by then. His childhood fascination with the circus and the Grand Guignol also governed his cinephilia in these early years. His favourite films were American comedies by Chaplin, Keaton, Harry Langdon and the Marx Brothers. It was only after he came into contact with the circle of Ettore Scola, Cesare Zavattini, Aldo Fabrizi and Roberto Rossellini, that he would seriously consider the cinema as a medium of expression.

Fellini’s collaboration with Rossellini would prove important to both men. He contributed to the dialogue of neorealist classics such as Rome, Open City, Paisan and also worked as an actor alongside Anna Magnani in the controversial short Il Miracolo. After collaborating with Alberto Lattuada on Variety Lights, Fellini directed his first solo feature, The White Sheik. Already visible is Fellini’s focus on the media’s influence on people’s private fantasies, a theme that informed La Dolce Vita and 8 ½. The White Sheik also marked the start of Fellini’s lasting collaboration with composer Nino Rota and most notably featured his wife, actress Giulietta Masina, in a brief cameo as a prostitute named Cabiria. Her comic performances channeled the spirit of silent cinema and directly inspired two of their most notable collaborations - La Strada and Nights of Cabiria. Both films won Academy Awards for Best Foreign Film. They also best illustrate the relatively restrained and sober style of Fellini’s early films. The visual style is closer to his neorealist beginnings with its content focusing on exploitation of people at the lowest level of society.

Under the aegis of psychologist Dr. Ernest Bernhardi, Fellini discovered the works of Carl Jung whose works inspired him to move away from the objective neorealist style to a subjective approach. Through use of a complex system of symbolism he would evoke a “collective unconscious” that enveloped his thoughts and feelings with that of his characters and the society they lived in. La Dolce Vita was the first film to display this new style. Made in 1960, this multi-episode narrative marked his first collaboration with Marcello Mastroianni, the actor who became his virtual alter-ego. The film became one of the defining portraits of Rome, a time capsule of the period of Italy’s economic miracle. La Dolce Vita received the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival and its success made Fellini world famous. The dark subtext of the film was the manner in which media organized modern life into a vacuous and superficial spectacle. This theme is borne out even strongly in The Temptation of Dr. Antonio, Fellini’s contribution to Carlo Ponti’s omnibusBoccaccio ’70. The title character is a censorious professor who slowly loses his sanity when a giant billboard of Anita Ekberg is installed across his apartment window. This short marked Fellini’s first use of color in film.

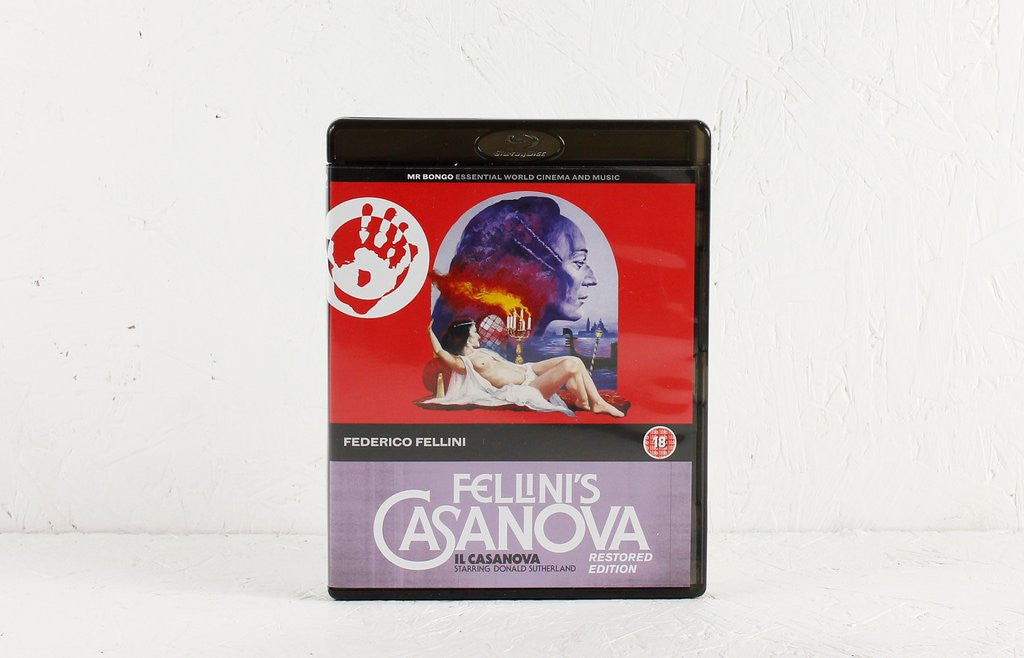

By 1963, Fellini had directed six features and three shorts; totalling them he concluded that the next would be, film no. 8 ½. This landmark film is regarded as Fellini’s masterpiece, a technical tour-de-force that is considered to be the definitive glimpse of an artist’s creative process. Fellini would depart even further away from the conventions of narrative cinema in his 70s films. Stories were organized around a mosaic of vignettes, often depicted in self-contained tableaux. Amarcord and Roma, which exulted in the director’s proud command of form, achieved critical and popular support. Casanova was praised for its visual expression but its cold gaze into the vacuous life of the legendary 18th Century adventurer alienated the usually supportive critics; it’s deliberate undermining of the erotic allure of the story marking it a challenging film. The films of his final period includes further collaborations with Marcello Mastroianni – City of Women and Ginger and Fred (also starring Giulietta Masina). But it was also marked with frustrations, owing to lack of funds for projects which remained unrealized. He received an Oscar for Lifetime Achievement in 1993, two months before his death. More than 70,000 people attended his memorial service at Rome’s legendary Cinecittá studios, a fitting celebration to a legitimate national treasure.