Although regarded as the greatest artist of Spanish cinema Luis Buñuel only made three films that are Spanish by nationality. His exile from his homeland at the end of the Spanish Civil War resulted in extended periods in Mexico and France. Despite this displacement, Spain was never far from Buñuel’s mind. The peasant culture of the villages of Calanda and Zaragoza, many of them dating to the Middle-Ages, greatly influenced his imagination during his childhood. The Spanish literary tradition, represented by Lope de Vega, Cervantes and the writers of picaresque stories, remained constant touchstones. Strongest of all was the distinctly Spanish nature of his Catholicism; he would retain its influence long after he renounced the teachings of the Church. At the University of Madrid his friendship with poet Federico Garcia Lorca and painter Salvador Dalí would play a major role in the avant-garde of the 1920s. It was during this period that he discovered the works of Sigmund Freud. His insight into the functioning of the unconscious and its relation to human sexuality would strongly inform the content of Buñuel’s films.

His visits to Paris during the 1920s would result in a lifelong association with the Surrealist movement. Their desire to change society through provocative works of art greatly inspired the young Spaniard as did their passion for cinema. Although a regular moviegoer throughout his life, it took a viewing of Fritz Lang’sDestiny (1921) for Buñuel to accept cinema as his vocation. Along with a stint as a film critic for art journals, he found work as an assistant to French director Jean Epstein. His first film was made in collaboration with friend and fellow surrealist, Salvador Dalí. Un chien andalou dazzled audiences with its density of ideas and the force of its images, including the famous opening where a barber (played by Buñuel himself) cuts a woman’s eye with a razor; one of the most famous scenes in film history. Its success inspired Buñuel to be even more brazen with his second film. L’Âge d’Or was a scathing satire on bourgeois society, its anarchic vision and anticlerical humor sparked riots at the film’s premier. It remained banned in France for nearly fifty years. His return to Spain marked a period of inactivity with the sole exception of Land Without Bread, a documentary on the region of Las Hurdes. The film was made only a few years before the outbreak of the Civil War.

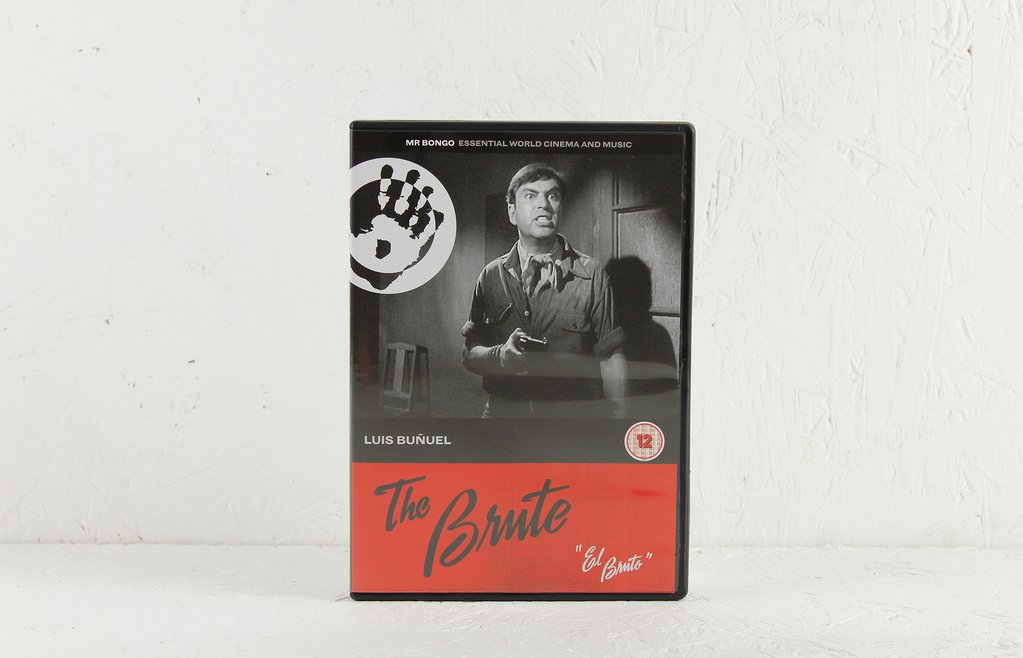

As a Republican, Buñuel was opposed to the policies of Generalissimo Francesco Franco. The latter’s victory and the resulting establishment of his dictatorship resulted in exile from Spain for Buñuel and his family. He would spend the duration of the Second World War as a film archivist at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. The post-war atmosphere of paranoia resulted in his loss of position on grounds of suspected atheism. Fortunately, this temporary period of unemployment was relieved as a result of his friendship with producer Óscar Dancigers. Buñuel returned to active film-making in Mexico’s film industry, where he enjoyed creative freedom and made 18 films over 14 years. Relatively commercial fare such asSusana and El Bruto display considerable skill and growing command of the medium. Personal films from this period, such as Los Olvidados, Él and Nazarín influenced directors like Nicholas Ray (Rebel Without A Cause) and Glauber Rocha (Black God, White Devil) while the film-makers of the French New Wave would cite the visual richness of The Criminal Life of Archibaldo de la Cruz. His time in Mexico also included two unusual English-language films; a colour adaptation of Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe and The Young One, an anti-racist parable set in America’s Deep South.

Buñuel’s collaboration with producer Gustavo Altratriste resulted in two films, Viridiana and The Exterminating Angel; the success of which would re-install him in the ranks of the world’s greatest directors. Viridiana (1961) marked a return to Spain; a bold satire on Franco’s conservative society, especially the collusion of the Catholic Church with the State. The film’s provocative humor and its suggestive visuals provoked outrage within the Spanish government and the Catholic Church. It received thePalme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival via a print smuggled to France by Buñuel’s son. Accusations of blasphemy only inspired him to be bolder in his critiques of religion in films like Simon of the Desert andThe Milky Way. His later films, made in France, allowed him great aesthetic freedom as a result of collaborations with producer Serge Silberman and screenwriter Jean-Claude Carrière. They also benefited significantly from a stock company of actors which comprised of Jeanne Moreau (The Diary of a Chambermaid), Catherine Deneuve (Belle de Jour, Tristana), Delphine Seyrig (The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeosie), Michel Piccoli, Francesco Rabal, and Fernando Rey who often played the director’s alter-ego. Despite being uprooted, his unique personality united the different periods of his career; whether in Mexico, Spain or France, his films remained Buñuelian first and foremost.