Born in Bologna in 1922, Pier Paolo Pasolini left behind a searing legacy that haunts contemporary Italy more than thirty years after his death. More than anyone, Pasolini gazed deeply into Italy’s role in the spread of Fascism and, more controversially, the continuing influence of its ideas in post-war Europe. For him, this was a matter of great personal significance; his father was a soldier in the Fascist Army (he had once protected Mussolini from an assassination attempt) while his brother joined the resistance only to be murdered in an ambush. This personal trauma coincided with a period of intellectual development as Pasolini engaged with Marxist philosophy; especially the works of Antonio Gramsci, the founder of Italy’s Communist Party (PCI). His relationship with the PCI, however, was tense. As a poet and intellectual, Pasolini scrutinized his fellow Communists as critically as he did bourgeois society. His enemies retaliated by targeting his personal life; the first instance being his 1949 expulsion from the Party when they learnt of his homosexuality. Employed as a teacher in the Udine city of the Friulian province, Pasolini lost his job and was forced to move to Rome with his mother.

Rome, however, proved to be the site of Pasolini’s artistic flowering. During his time there, he took various odd jobs to make ends meet. He lived in the shantytowns on the outskirts where the borgate resided. Pasolini was fascinated with their unique way of life, their unconscious subversion of Catholic rituals and bourgeois morals. His novel Ragazzi di Vita, published in 1955, was a chronicle of Rome’s lower depths; its non-judgmental portrait of criminal behavior earned it condemnation from both the ruling Christian Democrat party as well as the Communists. Federico Fellini, however, was sufficiently impressed with its wealth of detail and the accuracy of the dialogue to employ Pasolini as a dialogue consultant on Nights of Cabiria (1957). The resulting experience led Pasolini to consider cinema as a medium to express his eclectic ideas.

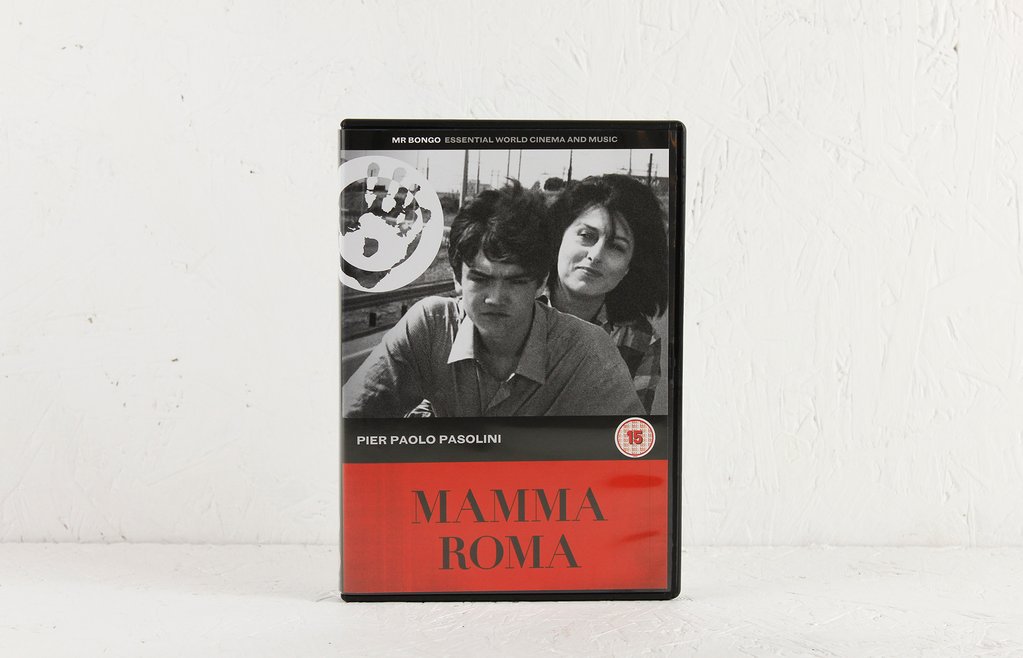

Bernardo Bertolucci, who served as Pasolini’s assistant on Accattone (1961), noted that the film’s visual style owed more to the Renaissance masters than the cinema. In his first film, the framings of the titular pimp (played by Franco Citti) and his fellow vagabonds hearkened to the religious paintings of Massacioand Mantegna. He continued in a similar vein with Mamma Roma, where the casting of Ettore Garofalo as the son of Mamma Ro (Anna Magnani) was based on his resemblance to a Carravaggio painting. Both films also took inspiration from Italian Neorealism with Anna Magnani’s casting in Mamma Roma a deliberate reference to her performances in Rome, Open City, L’Amore and Bellisima. Like Arthur Rimbaud, Pasolini’s art endowed a sacred dimension to those on the margins of society, outlaws whose lifestyle subverted the morals of the establishment. Pasolini’s use of religious iconography referred to the peasant origins of the Christian religion which the modern Church had strayed away from.

His 1964 film on the Life of Jesus, The Gospel According to St. Mathew was shot in the South of Italy. It was a “literal” reading of the chosen gospel, with dialogue drawn from the text. The film’s style was similar to Accattone and Mamma Roma in its casting of non-professionals and its eclectic musical and pictorial references. With the exceptions of Teorema and The Hawks and the Sparrows, all of Pasolini’s later films were adaptations of classic texts. These included Greek tragedies (Oedipus Rex and Medea) and the films which formed the ‘Trilogy of Life’ - The Canterbury Tales, The Decameron, The Arabian Nights. These period films aimed to portray the richness of peasant cultures by portraying its roots in the ancient world; highlighting its importance in the rise of civilization. These flights into the past, manifested as a result of Pasolini’s growing disillusionment with contemporary Italy. He decried the spread of consumerism in Italy which led to increasing homogenization, suppressing the proletarian culture he took inspiration from. His despairing vision was fully unleashed in Saló, which proved to be his last film.

The film was a loose adaptation of The 120 Days of Sodom written by the infamous Marquis de Sade; its setting was transplanted to the final days of the Second World War, in the Nazi-established Saló Republic. The film’s shocking violence made it one of the most controversial films ever made, subsequently banned in many parts of the world. Its notoriety is heightened by the fact that Pasolini was murdered two weeks before its premier. The circumstances of his brutal killing resulted in a cloud of speculation, further fueled by the Italian police re-opening the case in 2005. At 53 years of age, Pasolini achieved a considerable body of work, a cinematic oeuvre of stirring originality. For Bernardo Bertolucci, his sudden passing marked the end of an era in Italian cinema.