Satyajit Ray is one of cinema’s truest Renaissance men. In addition to his films, he is a reputed writer of short stories, a music composer (scores for his own films and other film-makers, notably Merchant-Ivory’s Shakespeare Wallah) and a painter and graphic designer of considerable skill. Appropriately enough, Ray derived from a background of great culture, the son of poet Sukumar Ray who died when he was three years old. His interest in fine arts, literature and painting led him to reside at Rabindranath Tagore’s Santiniketan (an intellectual retreat for artists and thinkers) for a significant period of time. Ray’s true love however was the cinema. The cinema of 30s Hollywood, which included Fred Astaire musicals and comedies by Ernst Lubitsch; Russian films he devoured in repeated viewings at the Calcutta Film Society (which he co-founded in 1947) and later the Italian neorealist films which he discovered in London.

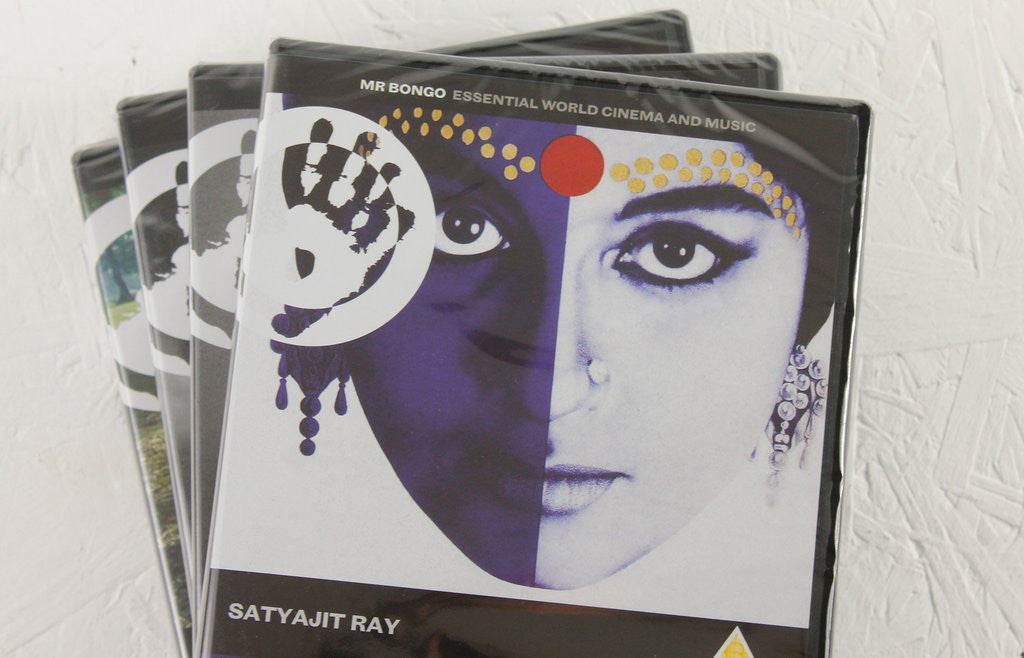

At the time of the Second World War, and the final period of India’s Independence struggle, Ray was employed as a graphic artist at a publishing house in Calcutta designing covers of books as well as illustrations of content. One of these books was Bibuthibhushan Bandhopadhyay’s Pather Panchali which immediately inspired Ray as the subject for his first film. Ray received further inspiration when he met French master Jean Renoir during pre-production of his Bengal-set The River. His visits to the set of The River formed lasting friendships with art director Bansi Chandragupta (who became Ray’s regular art director) and future cinematographer Subrata Mitra. Pather Panchali (Song of the Little Road), released in 1955 after a difficult three-year production would be the fruit of Ray’s tenacity and uncompromising will. Made with an inexperienced cast and crew outside the system of commercial Indian cinema, the film became a great international success winning a special prize at the Cannes Film Festival.

Ray alternated the three films of The Apu Trilogy with period films that critically examined the decline of Calcutta’s ruling class. The Music Room chronicled the lonely final days of a decadent landlord while Goddess was a bold exploration of religious values in Indian society. An omnibus adaptation of Rabindranath Tagore’s stories, Three Daughters (released internationally as Two Daughters, without its middle section) provides a summation of Ray’s early period. The lyric poetry and understated drama of Pather Panchali achieves great poignancy in The Postmaster’s depiction of class values in human relationships. Despite being categorized as a socially conscious film-maker, Ray eschewed didacticism and overt political statements. His work, characterized by understated acting and avoidance of melodrama were nonetheless highly stylized works. Ray evoked the inner life of his characters by cinematic means of composition, lighting and cutting, all of which were meticulously planned and choreographed.

The films of the “Calcutta Trilogy” – The Adversary, Company Limited and The Middleman – were ambitious portraits of post-Independent urban India. These films depicted Ray’s boldest shifts in style, moving from deadpan satire to stark expressionism. They also depicted a gradual darkening of Ray’s vision as he portrayed the corruption and squalor of modern India. Likewise, Ray’s explorations of Indian history – The Chess Players, Distant Thunder, The Home and the World painted similarly ambivalent portraits of life under colonial rule. His final film, The Stranger ends his career on a hopeful note albeit hope coupled with resignation and defeat.